WOBO Governor David Gibson is pleased to share information received from Create Digital in respect of engineering research and activities.

Five standout examples of land reclamation From Singapore’s Marina Bay to the Dutch polders, these land reclamation efforts exemplify the peak of engineering innovation.

From Singapore’s Marina Bay to the Dutch polders, these land reclamation efforts exemplify the peak of engineering innovation.

Urban development along coastal areas, particularly in Asia, is often facilitated by land reclamation efforts.

These might be relatively minor, such as the construction of an extended sea wall to fortify a coastline against erosion, or significant, such as the creation of entirely new island networks.

Here are five countries that have used land reclamation to expand their borders, counteract environmental effects, or improve community experiences.

The Passivhaus concept is an approach to designing sustainable structures by using engineering to work with, not against, the natural environment.

The Canadian city of Regina was built on treeless prairie at a latitude of 50 degrees north.

Temperatures in January fall to an average of minus 20°C, but summer brings its own challenges: the highest July temperature recorded in the city is 43.9°C.

It is a harsh environment for human habitation at the best of times, but during the 1970s oil crisis that saw energy prices skyrocket around the world, Canadian mechanical engineer Harold Orr sought to develop building techniques that could work with the environment to minimise the cost of heating and cooling.

Orr led the construction of what would become the Saskatchewan Conservation House: a Regina home that was designed to be extraordinarily airtight, with highly efficient insulation and controlled airflow.

Compared to the average 1970s home, the building used 85 per cent less energy.

As oil prices returned to normal, Orr’s approaches began to fall out of favour, but the idea of super-efficient building techniques didn’t disappear. Sweden and Denmark imposed low-energy building standards in the 1980s, and in 1988, Swedish engineer Bo Adamson and German physicist Wolfgang Feist launched a concept they called Passivhaus.

They defined this as a building with an extremely low energy demand, and so would require no active heating.

By 1990, they had constructed a pilot Passivhaus in Darmstadt, Germany, and Feist went on to found the Passive House Institute in 1996.

Today, more than 120,000 buildings around the world are certified as meeting the exacting Passivhaus standards. Just 25 of these, however, are in Australia.

Solving Australia’s solar panel waste problem

With total volume projected to reach one million tonnes by 2035, tackling the issue has become a top priority for manufacturers.

Solar panel waste is projected to reach one million tonnes by 2035. Effective management of this problem is fast becoming a priority for Australian manufacturers.

Managing the waste from rooftop solar and solar farms reaching the end of their lifespan might seem like an insurmountable undertaking – but there’s increasing incentives to tackle the issue.

The total value from materials that could be extracted from solar panels at the end of their life, for instance, is projected to exceed AU$1 billion by 2035. Plus, there’s the obvious boon to the environment from reusing or recycling parts rather than disposing of them in landfill.

This makes end-of-life management of solar panels of vital importance for innovation, economic and sustainability reasons.

The geotextile pollutant barrier that removes harmful PFAS from soil more effectively and sustainably.

In the late 1940s, a new set of chemicals was developed that revolutionised the manufacture of everything from cookware, clothing and food packaging to firefighting foam, cosmetics and medical devices.

Per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) could repel water, oil and stains so quickly became widely used on thousands of products, including Teflon, impermeable clothing and footwear, dental floss, cosmetics and artificial turf. They are also the reason why the grease in pizzas doesn’t seep through the cardboard boxes.

However, in the 1990s, scientists realised that PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals” due to their resistance to degradation, had found their way into waterways, soil, fish and other animals. Tests revealed that they were also commonly present in human blood, and could be harmful to health.

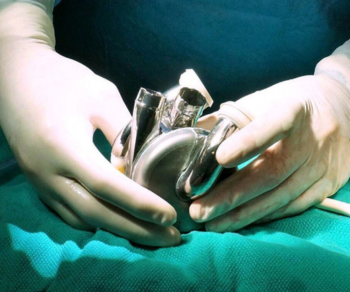

How an Aussie engineer created an artificial heart

The world’s first long-term artificial heart won’t wear out, age or break – and it’s about to be implanted in human bodies for the very first time.

Using magnetic levitation technology, the world’s first long-term artificial heart won’t wear out, age or break. It’s small enough for a child’s chest yet robust enough to pump life into an active adult, and it’s about to be implanted in human bodies for the very first time.

Back in 2000, when Daniel Timms was completing his mechanical engineering degree, his father suffered heart failure. It was an experience that would shape his life’s focus.

“For my PhD I decided to look at artificial heart technology as something that might be able to help him have a better life,” the Australian biomedical engineer told create.

Timms hails from a family where engineering solutions were dinner discussions. He and his father, a plumber, would often tinker with ideas to craft the right kind of heart pump.

World’s biggest single-train ammonia plant

This $6.4 billion project is expected to shift Australia from being a net fertiliser importer to a net exporter

The global ammonia market, which reached around 167 million t in 2021, is expected to increase at a compound annual growth rate of 7.22 per cent from this year to 2030.

With the ammonia industry growing rapidly, numerous ammonia projects are taking off across the globe – including the Perdaman’s Project Ceres, a major Urea plant, in the Burrup Peninsula, approximately 10 km from Dampier and 20 km north-west of Karratha on the Western Australia coast.

Clough and Saipem, in a 50/50 joint venture, were chosen to develop Perdaman’s project. The scope of work includes engineering, procurement of equipment and materials, construction, pre-commissioning and commissioning for the execution of a latest-generation fertilisers plant with a capacity of 2.14 million t of urea per year. The facility will have a syngas production block, fertiliser production block, and offsite facilities and utilities.

Replacing the Fitzroy River Bridge

When part of a vital regional river crossing collapsed, engineers raced to design a replacement bridge that could withstand heavy flooding.

The Great Northern Highway in Western Australia’s Kimberley region provides a vital overland link between Broome and Darwin.

When a bridge over the Fitzroy River 400 km east of Broome was severely damaged during flooding caused by Tropical Cyclone Ellie in January 2023, engineers raced to design and build a replacement bridge that could withstand heavy traffic, adverse weather forces and flooding.

The team managed to deliver the project an entire six months ahead of schedule and in time for the start of the following wet season.

Reducing plastic’s stranglehold on the planet

Plastics account for the lion’s share of marine waste, and we only recycle a fraction of it in Australia. But a new recycling technique could transform how households dispose of “scrunchable” plastics.

We’re in the midst of a plastic pollution crisis, with plastics expected to outnumber fish in the ocean in just over a quarter of a century.

Australians consume a sizable amount of plastic, including 70 billion pieces of soft or “scrunchable” plastic, such as food wrappers, each year, with only 13 per cent of plastics actually recycled.

As our oceans choke on plastic, use is increasing – and is expected to double by 2040.

But a team of researchers from the University of New South Wales led by Dr Vipul Agarwal and Professor Per Zetterlund are on the way to cracking the plastic recycling problem.